Hallucinations, a blog about writing, trains, and Wire to Wire

Browsing Category: Writing

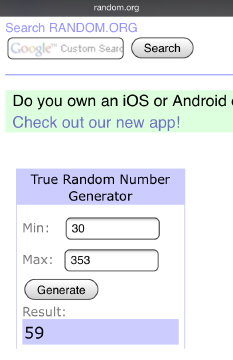

Pick A Number

I’ve been using a random number generator lately to help me edit my manuscript. I started by printing the whole thing out and putting it in one of those cheap, plastic comb binders. It’s 353 pages, but I don’t want to mess with the first thirty right now. So, when I’m editing, I go to Random.org and set the parameters at 30 and 353. It generates a number, and I go to that page and make any changes on the hard copy. Then I get another number and go to that page, working my way randomly through the manuscript.

There are 50 pages left now, so frequently the number takes me to a page I’ve already done—in which case I just find the closest unedited page.

Why am I doing this? Mainly because I find it much less painful this way. I kind of dread going through the manuscript sequentially, but I don’t mind reading individual pages. This way keeps me from getting bogged down in bad spots, and I’m not tempted to change the story. It helps me look at sentences with a much more specifc attention. Oddly, the random sample helps me stay alert to tone and consistency. Finally, it adds an element of playfulness that I think is really helpful. It reminds me that while I want to be productive, I also want to have fun.

So, back to work. The number I just got is 59.

------------------------

>

I've got your number right here. New video by Miley Cyrus.

Posted in Writing

The Strip Club and the Grange

Okay, I didn’t actually do a reading in a strip club, despite various statements that I may have made on Facebook and elsewhere. Not everything you read online is true – I mean, I'm trying to promote a book here.

And technically, I did do a little reading in a strip club – Portland’s Club Rogue – but only as part of a video shoot for the book trailer. No one else was there except the film crew from Juliet Zulu, Tony Perez from Tin House, and Sandria Dore, a dancer who was oddly unimpressed to meet an author. Although that was in the script, so maybe she was just staying in character.

We were filming in Club Rogue because Michael Slater, one of the main characters in Wire to Wire, has a habit of going to strip clubs at various points in the book. He doesn’t go to see naked women, however. He goes there to feel the fear of exposing his loneliness and need:

“One dancer in particular had his number. She made him look left, she made him look right. She had him on a little string. She was extremely good-looking and the fear she inspired scoured a month of crap off his soul.”

.jpg)

And yes, that's a Bob Seger t-shirt I'm wearing. Perhaps another reason why the stripper ignored me.

After the shoot, just to see what it felt like, I stood by the pole and read to the empty room as the film crew packed up. I’ll be replicating this experience in bookstores soon, minus the pole, but hopefully with an audience. The tour schedule is here. Come and make it rain.

_____

I did, however, read, at the Springwater Grange in Estacada, Oregon, last Saturday night. Friends, acquaintances, and passers-by who were quick to believe that I gave a reading in an empty strip club were suddenly doubtful when I claimed to have read in the Grange Hall. People, you’ve got it backward – the Grange was amazing. Writers Night at the Grange was like three levels better than the best reading you can possibly imagine.

It attains that status through the goodwill, generous heart and friendship of Stevan Allred, who has organized the event for the Estacada Area Arts Commission for the past nine years, and from Joanna Rose, author of Little Miss Strange, who teaches with Stevan at the Pinewood Table and shares the stage with him at the Grange.

Every year, a third person is invited to join in reading – often one of their students – and this year it was me. Go ahead, take a guess as to how many people come out on a Saturday night in Estacada to hear writers read. Nope, you’re low. Double it. Still low. I counted nearly 70 people. It was an amazing experience – a perfect, confidence-building way to debut Wire to Wire and start the book tour.

The theme of the night was On the Road. Joanna read a beautiful piece about a road trip through rural Oregon, snow, and memories. Stevan read an essay about a real 1970s freight-hopping trip that took me back to my youth – reminding me that, originally, I jumped freight trains for the same reason Slater visits strip clubs – to scour the fear off my soul.

After the reading, there was a huge party at Stevan’s house, as there is every year. When I say it was a terrific time, that’s true. When I say I regret starting a fight and stabbing a guy, that’s not. But feel free to spread the rumor. I’ve got a book to promote, and I could use the buzz.

Thanks to Juliet Zulu for the production still at Club Rogue, and fellow writer and previous Grange-reader Steve Denniston for the shot of me at the podium.

_________

Say it takes you an hour to drive through rural Oregon to the Springwater Grange. Say you've been waiting for this all your life. Roll down the window and play this fucking loud. Steve Earle, "Feel Alright."

Posted in Trains | Wire to Wire | Writing

Louder

Next weekend I’m reading an excerpt from Wire to Wire at the Springwater Grange in Estacada, Oregon. It’s a big room, and I’ve been practicing for it, working on getting it loud.

I can do loud, but I don’t do it naturally. My speaking voice is normally a little bit quiet. In fact, a long time ago I adopted the line from the B-side song “The Quiet One” by The Who: I ain’t quiet – everybody else is too loud. (For younger readers, The Who are an a cappella group from Leeds, known for their delicate harmonies.)

On the other hand, when I started learning fiction, my writing voice was the opposite of my speaking voice: I always wanted the writing to be loud. A blast of voice is how I would describe my early style now, though at the time I called it incantatory – because I had read that Kerouac and Joseph Conrad, both of whom I liked, were incantatory writers. I wanted sentences that went on for pages, doubled back on themselves, and emptied the bench of every punctuation mark known to man, especially semi-colons. Dashes were good too.

Of course, I was doing this at about the same time Raymond Carver was revitalizing the short story with short, direct sentences that displayed exactly the opposite signal to noise ratio. (In Carver’s case, all signal, no noise.) My allegiance to the sound of a sentence (caring more about how the syllables fell than the story being told, would be a harsh way of putting it) might have been an early warning sign of the long road ahead. But I wasn’t deterred.

In fact, I once sent a friend an unmarked cassette tape with a message, written in Sharpie, probably in all caps, that said: “This is how I want my writing to sound.” On the tape was an Elvin Jones drum solo. I bought some of his albums to listen to when I wrote.

(And I still have them. Filed under J right next to Joan Jett. Go ahead - imagine me as a vinyl aficionado if you like. It’s not really true, but I like the way aficionado sounds on the page. Which explains why I once changed my name to Johnny Revillagegado for a very brief time. But that’s a whole nother post, as we would say in Michigan.)

Eventually I finished a story built around voice. It opened like this:

It was a new time and we rode slam hard, rode it on flatcars and hoppers and bulkhead flats, in empty woodchip cars, gons, auto ramps, and piggies all over the west, the prairies and dirty western towns of district nine, Kalama, Lillooet, Sutter’s Portage, dozens of towns seen from the frame of a boxcar and eyes numb past blinking. Towns of dust where dirty kids threw rocks at the train – in laziness, not maliciously – and empty towns on the straight flat where the last lit beer sign burned thirty miles into the night.

The story worked, sort of – it got published in a low-circulation newsletter – but soon I discovered the limitations of voice (like the problem of wearing the reader out). And I started reading Robert Stone. Since then I’ve read the opening sentence of Dog Soldiers about 7,000 times. “There was only one bench open in the shade and Converse went for it, although it was already occupied.” A setting, a character, and an action, all in 19 fairly quiet words. My admiration for that, and for the rest of the book, started me on a new path – one of looking beyond voice. Beyond loud.

_____

I would still be lost on that path today – wandering through the woods, eating acorns, clutching an unfinished manuscript for warmth – were it not for Stevan Allred and Joanna Rose. Stevan and Joanna teach writers in Portland at The Pinewood Table, named for the table in Joanna’s living room. I joined the group in the early 2000s, thinking I would stay for five weeks or so. I stayed for five years instead. I read every word of Wire to Wire around that table; the parts that puzzled me most (and there were lots of them) I read two or three times. If not for Stevan and Joanna and the other writers at the table (from whom I learned nearly as much) there would be no book, no blog, no readings. Among the many things I learned at that table was when and how to stop writing Wire to Wire.

Stevan and Joanna are both reading at the Grange this coming weekend – Stevan organizes the Writers Night event once a year. This year, the theme is "On the road." I’m thrilled to be reading there with them. I’ll be going to a lot of great bookstores this summer – places I’ve always dreamed of reading. But nothing could be more perfect than starting with Stevan and Joanna at the Springwater Grange in Estacada.

As far as I’m concerned, if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere.

____

Elvin Jones explains how to build a drum solo around the melody of "Three Card Molly."

Posted in Wire to Wire | Writing

This is not my book

Wire to Wire: Inside the 1984 Detroit Tigers Championship Season is not my book. Though in a way it is. This other Wire to Wire, written by George Cantor and published in 2004, chronicles the magical year when the Tigers opened the season with a 19-1 record.

Imagine it happening day by day. 19 wins. One loss. A few weeks later they were 35-5. During the first quarter of that season, the Tigers were virtually unbeatable. Argue great teams all you want, but based on that win-loss record, no team in baseball has ever been that good, before or since.

The Tigers won the pennant and the World Series wire to wire that year – meaning they were in first place every day of the season. Only two other teams had ever done that in over 100 years of baseball.

I took that as a freaking sign. I named my book after it. (Cantor's book, I might add, had not been written yet.)

Later, I wrote to Jesse Burkhardt about my decision to quit my job and write a book. Jesse is also Iron Legs Burk, who showed me how to hop freights. He saved the letter for a decade or two, and today he mailed it back to me.

.jpg)

To be clear, my Wire to Wire has nothing to do with baseball. The Tigers aren’t even mentioned. (Well, actually, there’s a little play by play in the background of one scene, an argument. If you read the book and you’re from Michigan, imagine the great Ernie Harwell calling the plays as Harp and Lane shout at each other.)

Stripped of the Tigers' connection, the phrase wire to wire had to find its own meaning in my story. And eventually it did. The necessity of discovering what it meant was a blessing I didn’t recognize at first.

The letter continues:

Near the end of the letter, the younger me also writes this to Jesse: “There’s a line in my book that says ‘we rode the rails and we kept going long after most people would have quit.’” That particular line is no longer in the book – the voice is wrong – but now it seems to apply as much to writing as it did to riding. I kept going. The strength came from a lot of people, Jesse and many others. It came from music, my family, from random good luck that fell on me for no reason – and even from a baseball team that, during one amazing year, simply couldn’t lose.

______

I’m part way through Cantor’s book, by the way, and if you’re a baseball fan, or a Sparky Anderson fan, I think you’d enjoy it. I also have a new phrase in my head – a phrase that still needs to find its meaning. I'm taking that as another good sign.

______

In a world like this, you need a heart like Jon Dee Graham's. So you don't get "Faithless."

In a world like this, you need a heart like Jon Dee Graham's. So you don't get "Faithless."

Posted in Wire to Wire | Writing

What dreams are really made of

I’m unclear about the rule concerning dreams and fiction. Some say you should never write about dreams – after all, fiction is itself a kind of dream, so any dream you put in a book is automatically a dream within a dream. Plus they’re just never as interesting as real life ('real' fictional life, I mean).

Others say dreams are like sex scenes – they’re okay as long as they’re justified, but keep it short and no more than three per book.

Wire to Wire includes five dreams, but three of them are super short – a sentence or less – so I think I’m under the limit. (You’ll have to count the sex scenes yourself.)

The desire to write about dreams is understandable, though. There you are, struggling to create a believable imaginary world, and every night your subconscious is churning out a nonstop stream of surreal, autobiographical fiction. Why not use some of that stuff? Plus, no one wants to hear about your lousy dreams in real life, so your only option for sharing is to put them in your book.

(For the record, none of the dreams presented in Wire to Wire started out as actual dreams, except one. And it’s not the Blowjob Dream. I wish.)

Still, I do agree that you have to be very careful about using dreams in stories. By their nature – ephemeral and shifting and unreliable – dreams lack many of the things that make fiction seem real to the reader.

Happily, there are no restrictions about using dreams in blogs. In my view, anyway, blogs are like early Deadwood episodes. It's a land with no rules and anything goes – at least until George Hearst shows up and spoils everything.

So in that spirit, I present: Things I’ve learned from my dreams in just the last seven nights.

- If your testicles come off, go to whatever hospital is close by. Don’t try to drive to a better hospital way across town, because you’ll inevitably get drawn into some other scenario, like a pick-up basketball game. And you’ll never get your testicles back on.

- If there’s a switch on your desk that turns gravity on and off, make sure there’s a similar switch on the ceiling.

- A screen door mounted with duct tape instead of hinges is not adequate protection against albino wolves.

- Also, if you attach your screen door using duct tape, try giving your roommate a heads-up, so he doesn’t accidentally rip it off just as the albino wolves are approaching.

- Strippers prefer customers who smell nice over customers who look nice. (Actually, I didn’t learn this from a dream. I learned it from Twitter. Strippers are among the most interesting people on Twitter, in my opinion. Generally, they aren’t there to promote something the way the rest of us are – they’re just sharing their observations about their generally crappy but interesting jobs. Most of them – at least the ones I follow – seem pretty empowered. Their jobs have many of the same drawbacks that our jobs have, but intensely amplified, so there’s more drama. And the language of strip clubs completely lacks the deadness of the non-stripping world. This particular observation about good-smelling custys comes from StripperTweets – currently tweeting from Austin, where she is on a panel about interactive something-or-other at SXSW. I’ve also learned a lot from K to the A to the T. I hope to meet them both someday and buy a table dance, or at least give them an ARC.)

- If there’s any sort of high school gym involved in your dream, trouble will follow. Locker rooms are especially bad.

- Sex in the subconscious is almost always a one-dream stand.

- If you order a drink at a coffeeshop, and another customer picks it up, hit them with a blindside tackle, pin them to the floor, and lecture them about their incredible sense of entitlement. (More of a fantasy than a dream, admittedly.)

- And finally, if you’re standing in the living room of a house you no longer own, and a tornado is coming your way, perfectly framed in the picture window, don’t try to take a photo of it with your Nikon camera, because there won’t be any film in the camera, and even if you have a spare roll somewhere, you will have forgotten how to load it.

This last one is a hard lesson to learn. It make take 40 or 50 repetitions of this dream before you get the point. Going digital won’t help, either. The camera jams.

Here’s what puzzles me though: I never dream about my book. I dream about my dad, mom, wife, son, sister, and friends. I dream about freight trains, Michigan, Bob Seger, my job, and sex. I dream about editing my college newspaper (the pages are all blank). Why no dreams about the thing I’ve dreamt of most?

______

Michigan Dreams: "There are phantoms all around me, but they're just beyond my grasp." Country Joe and the Fish, "Bass Strings."

Posted in Writing

Things to worry about, and having faith

When my son was one minute old, he taught me something about life. The nurse handed him to me and in those first few seconds, I felt relief. The months of anxiety were over. My naïve thought was: I can stop worrying now. I held onto that belief for as long as it took to exhale and draw in one breath. Then I realized my worries weren’t over. They were just beginning.

So I guess what I learned was: It never ends.

Zane’s eighteen now. Things have more or less worked out. Still, last night my wife woke up around midnight, worried that he didn’t have enough gas to get to school in the morning. I could hear rain hitting the window. I almost asked if she wanted me to go out and check the gauge. But I didn’t. Never ask a question you don’t want to know the answer to.

A manuscript is like a kid that way, at least for me. The day Tin House said they’d take my book, I thought I’d reached the finish line. Instead, there’s a whole new universe of things to obsess over. Should I be promoting it more? Am I tweeting too much? What if Tin House has changed their mind about publishing it? I haven’t heard from them in a while. Should I call them just to be sure? What about reviews? Should I even read them?

Last Sunday I finished Tom Grimes’ brilliant memoir, Mentor. It’s the story of Grimes’ life as a writer and his time at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Grimes’ mentor is Frank Conroy; their relationship is at the heart of the story. It’s an amazing book. Publishers Weekly gave it a starred review.

Initially, I thought the appeal of reading Mentor would be in seeing the path I didn’t take. At about the same time Grimes went to Iowa, I quit my day job, started freelancing and tried to teach myself to write fiction. I thought it would take five years. It took much longer.

But although those two paths are different, they have something in common. A writer’s life is irrational, as Grimes says Conroy says. And you inflict all sorts of crap on yourself along the way. Irrational worries. Twice I put the book down and said, that’s enough. It’s too close to the bone. The problem is, it’s not the kind of book you can stop reading.

When I finished Mentor on Sunday night, one gift it gave me was a sense of resolve. I promised myself not to let the world define Wire to Wire for me. Reviews don’t matter.

The world, being a kind and gentle place, let me hold onto that belief for almost 12 hours before outing me as a hypocrite. The next morning Publishers Weekly gave Wire to Wire a starred review and made it Pick of the Week.

So hold that thought. It turns out reviews do matter. As long as they’re good. As for my resolve not to read them…hey, revision is everything in writing. That includes revising my beliefs.

Somebody tell me if I’m tweeting too much, though.

_____

Sometimes you gotta lose it, just to lose it, just to find it again: Alejandro Escovedo says you gotta have “Faith.”

Posted in Wire to Wire | Writing

Bad Advice for Writers

Writing a novel? First, you’ll need one of these. The Kaypro II. It comes with 64 KB of RAM and two double-sided, double-density drives for your 5 ¼ inch floppy disks. Encased in aluminum, and at just 29 pounds, it’s completely portable. Mine set me back about $1,800, but the price may have come down since 1983.

Sure, you could go cheap and try to write your masterpiece on a typewriter, but that’s gonna take forever. With the Kaypro, you can cut your novel-writing time to under three decades, tops. Sounds unbelievable, but I did it, and you can too.

Here’s what makes the Kaypro such a time-saver. Let’s say you’ve written the following paragraph as a first draft.

“Dexter Company had the school photo business from all over the state; Slater’s job was to develop rolls of photo paper. He ran a machine called the Silva, twenty-five feet of tanks and drums and torque, and he worked in the dark, listening to the hum and talking to the machine, his eight hours of competence and solitude, his rap and discourse in the dark. The whine of the rollers sometimes reminded him of freight trains crossing the Rockies, metal grinding against metal like the sound of violins being played under water. After he was fired, he imagined the Silva on the hot desert land outside Dexter Company, decaying, fulgent, a strange tribute to the gods or some fantastic drum set of the industrial age, after everyone got tired of the music.”

The first thing you’re going to want to cut is that line about violins being played under water. No one knows what that sounds like, with the possible exception of Lloyd Bridges. Who, sadly, is no longer with us.

On your old Selectric, you’d have to retype the whole thing just to lose that one phrase. Not so with the Kaypro. Simply mark the beginning of the phrase with ^KB. Then hit ^F repeatedly until you come to the end of the phrase. Mark it with ^KK and then enter ^KY. Magically, the offending phrase disappears. Or you could move the phrase somewhere else with just another 13 keystrokes.

Next you’ll want to change Slater’s name to Stryker, and then to Trager, and then to Stone, and then back to Slater. You’ll want to get rid of that part about “fulgent,” too. Also that whole section about “rap and discourse in the dark.” That’s a little weird. Take that out. Then put it back in. Then out. See how easy the Kaypro makes everything? Suddenly you have a zillion choices for every single line.

Later you may realize that it’s not Slater who works in the photo lab, but some other character, and it’s not in the desert, but Northern Michigan. You may decide to cut the passage entirely. No worries. The Kaypro runs on the reliable CP/M operating system. However, depending on how much time has passed, your floppy disks will need to be converted to Apple’s operating system before you can make any changes to your novel, or work on it in any way, including simply reading it. And while computer science has not yet invented a way to convert CP/M to Apple, you can get some mail-order software from Ohio that will convert everything to MS/DOS, supposedly, if you can find an old Dell or something. Then you could convert that into Apple…or you could just retype the whole damn thing.

If you still have that Selectric.

_____________

Bonus bad advice: To get a Kaypro II of your own, build a time machine, travel to 1983 and bring one back "Duty Free."

Posted in Writing

Three Clippings

I haven’t read my book yet. The advance review copy of Wire to Wire sits on my desk glowing sedately, like a night light, only more golden. “It’s not for reading,” I tell people, “it’s just for looking at.” Some of my friends have disregarded this advice and read it anyway.

I guess the reason I haven’t read it yet – in book form, anyway – is that it’s the last step in a long process, and I’m not quite ready to take it. But being near the end has made me think about beginnings, which in this case includes three clippings.

The first is an interview with Dylan from the early 1980s, of which I saved only the last few paragraphs, now on very yellowed newsprint. In it, Dylan says:

“You can only pull out of the times what the times will give you…Everything happened so quick in the ‘60s. There was an electricity in the air. It’s hard to explain – I mean, you didn’t ever want to go to sleep because you didn’t want to miss anything. It wasn’t there in the ‘70s and it ain’t there now.

“If you really want to be an artist and not just be successful, you’ll go and find the electricity. It’s somewhere…”

When I first read this, I was working for the electric utility in Seattle. I dealt with electricity all day long, but it was obviously the wrong kind. I needed to find Dylan’s electricity.

Not too much later, I quit my job, drained my small retirement account, and started writing the book. This explains why I am not retired and living in a big house off Green Lake Park.

The second clipping is from the mid-1970s. My mom sent it to me. She never overtly tried to stop me from hopping trains – knowing her efforts would be futile – but she sent me a news story about some kids who climbed on top of a moving boxcar and got hit by a power line.

I scoffed at this story. Those kids were partying, I told her; they weren't serious freight-riders. But I saved the clip, and it inspired the prologue of Wire to Wire.

I found the third clipping on a sad day. My father had died, and my mom was in poor health. Eventually, and not entirely of her own will, she came out to Oregon to be closer to my sister and me. Our family house in Michigan sat closed up, but essentially as she left it. After a while we had to sell the house, and I flew back to clean it up.

I found the third clipping on a sad day. My father had died, and my mom was in poor health. Eventually, and not entirely of her own will, she came out to Oregon to be closer to my sister and me. Our family house in Michigan sat closed up, but essentially as she left it. After a while we had to sell the house, and I flew back to clean it up.

It’s a strange thing to be alone in a house that no one has touched for almost a year, especially if it’s a house you’ve spent a lot of time in with other people around. When I walked in, the floors creaked like ice cracking on a lake.

I made a tour of the house, then sat on the couch. My mom saved newspapers and there was a small stack on the coffee table. A headline on the top one read: “Harsh fate awaits many.”

I sat there and stared at that for a while. It was a dark thought, certainly. And the editors were sugarcoating it with that last word. Many?? What about freaking all?

When I opened the paper up, I saw the article was actually about retirement planning. Harsh fate awaits many who fail to save for the future, was the full headline. But it was too late. The first half of the line had already cast its spell on me.

These days a new clipping is floating carelessly around my desk. Farmers find body surrounded by money, it says. It’s a sad couple of paragraphs about a woman found murdered in Eastern Oregon. My wife noticed it a few days ago and picked it up. “Why are you saving this?” she asked.

I have no idea, was my almost honest answer.

Maybe there’ll be some electricity there.

What about you? What clippings have made your desk their home?

___

Advance copy of WTW: "Will it glow at night? Will it make a hum? Will it look good with the rest of my furniture? Show me how this thing works," by Cracker.

Advance copy of WTW: "Will it glow at night? Will it make a hum? Will it look good with the rest of my furniture? Show me how this thing works," by Cracker.

(Runner-up: "A Day in A Life" -- I read the news today, oh boy. By a new group I just discovered on iTunes. Keep trying, fellas, and maybe someday you'll be the Blog Song of the Day.)

Posted in Wire to Wire | Writing

Burn down the barn

A farmer wakes up and sees his barn is on fire. You’re writing the dialogue – what does he say? That was one of the questions the writer Jack Cady posed to us in his fiction class.

When I said in my earlier post that I knew nothing about fiction when I started Cady’s class, I meant I knew nothing. Well, I knew enough not to raise my hand.

I could see the hypothetical farmer clearly enough. Picture Iowa, Cady said. A farmer alone in his kitchen, a cup of coffee in his hand. It’s a beautiful fall day – because terrible things happen on beautiful days – and the sun is just coming up. Through the screen door, the farmer sees the flames. Now he speaks. What’s his line?

I could see the hypothetical farmer clearly enough. Picture Iowa, Cady said. A farmer alone in his kitchen, a cup of coffee in his hand. It’s a beautiful fall day – because terrible things happen on beautiful days – and the sun is just coming up. Through the screen door, the farmer sees the flames. Now he speaks. What’s his line?

I kept my mouth shut. All I could think of was, “The barn’s on fire.”

Or worse, “Oh, no.”

Or worse still, “Wow, look at those flames.”

None of that made any freakin’ sense. The farmer was alone in his kitchen – who the hell was he talking to??? Plus, the reader already knows the barn is on fire.

So I sat there hoping I wouldn’t get called on. I remember the moment so vividly, a couple decades later, because it was one of those times when you come face to face with the depth of your own ignorance. And by you I mean me.

Instead, other people suggested lines, not much better than mine, which was okay with Cady. Play with it the way a child would play with it, was his mantra. Try things. Make mistakes.

After he heard our suggestions, he told us how dialogue has to reveal character, and then he gave us his line: “Done it, didn’t they?”

I was hooked. Four words and I knew how stubborn the farmer was. I knew about the enemies he had made and how much he would risk in the name of what was right. I even knew what kind of woman his wife would need to be to share a life with such a man.

I’ve spent a lot of time since then looking at draft dialogue that didn’t feel quite right, thinking “Done it, didn’t they?” And I still don’t always get it. On a good day, with enough caffeine, I can make characters move across a room. But how do you get them to talk? Still, at least I know what the standard is, and how to make mistakes.

____

Songs with great dialogue: Dylan's "Isis," and "Highlands." And my current favorite, Chuck Prophet's "Hot Talk." What am I leaving out?

Recent Posts

Archives

- December, 2017

- December, 2015

- January, 2015

- November, 2014

- April, 2014

- March, 2014

- December, 2013

- September, 2013

- July, 2013

- March, 2013

- January, 2013

- November, 2012

- October, 2012

- July, 2012

- May, 2012

- March, 2012

- February, 2012

- December, 2011

- November, 2011

- October, 2011

- September, 2011

- August, 2011

- July, 2011

- June, 2011

- May, 2011

- April, 2011

- March, 2011

- February, 2011

- January, 2011

- December, 2010

- ,

Categories

Links

- My Essay on Bloom: No Other Way Out

- Playlist in LargeHearted Boy

- A Book Brahmin Essay for Shelf Awareness

- Powell's Blog: Sex & Money

- Powell's Blog: Riding Freights

- Powell's Blog: Burning Down the House

- Powell's Blog: Bob Seger

- Powell's Blog: Thank You

- An Interview with Kathleen Alcala

- An interview with Laura Stanfill

- Video with Yuvi Zalkow

- Interview with Noah Dundas

- Tin House Blog: Motor City Fiction

- Blog on Occupy Writers

- W2W Essay for Northwest Book Lovers

- W2W Essay for Poets & Writers

- America Reads: Page 69

- America Reads: My book, the movie

- America Reads: What I'm Reading

- Interview with Be Portland

- The Oregonian: Where I Write

Subscribe to the RSS feed

Subscribe to the RSS feed